The Albion Beatnik Bookstore website (or how to change a light bulb in a tight space on a ladder)

The web page of the Albion Beatnik Bookstore, based once in Oxford, then Sibiu, always neo-bankrupt, now closed for business: atavistic and very analogue, its musings and misspells on books and stuff.

Bookshops I Have Known

In 1982 I was running books from a nearby market town, Aylesbury, to the provincial, academic avatar that is Oxford, to sell them on for what I regarded to be a great profit. These were the last knockings of days when the ‘runner’ existed, his or her (in fact always his) job to sell books from one shop to another. The mainstay of this alarmingly masculine second-hand book trade was incestuous: most provincial booksellers opened their doors each day to buyers from city shops, often specialist dealers, also runners; bookshop stock was priced often according to what this passing trade would pay (acknowledging their ten percent trade discount). A book might be passed from bookseller to bookseller several times before it was sold finally to a bona fide customer, the end user. This commercial book world worked because all of its components knew their rung on this hierarchical trade ladder. Before the age of the internet – now everybody can call up a book online and see what a notional value for it might be, although it is unlikely you will see the wood for the trees as you will chance only upon unsold books – there was an exponential price offered by booksellers, the rate dependent on their place in the economic firmament; that place was determined by geography, their speciality, their customer base and, importantly, the bookseller’s intent.

Some booksellers might never see a legitimate end user of any book they sold. Many of the old-time booksellers didn’t wish to, and some might even have cared little for their non-trade customers. Whilst the fraternity policed itself moderately well – dishonest dealers could be shunned within the trade – second-hand bookselling had a reputation for being historically dishonest at times. The trade had its share of drifters, chancers and no-hopers. Many of those who remembered these days of the wild west – of cowboys and customers – tended to pride themselves on their ignorance of books and their ostensible purpose, that is to be read; they sold them as though they were carcasses of meat. Some of the booksellers whose careers had started before the Second World War had sold their books originally from a barrow. Fred Bason’s diaries (four sporadically wonderful volumes, his vantage point offered fabulous if colloquial insight into so much more than bookselling) describe how market value was obtained: by starting the day selling all books at a certain (high) price; as the day progressed, the book’s price lessened on each hour. Customers would return at the designated point each day when the book they desired reached its appropriate value for them: open market value at its most unalloyed.

I worked at Weatherhead’s Bookshop in Kingsbury, Aylesbury for a few years, the most amazing experience. I began my time there haughty and superior, and I felt that Nick Weatherhead, the family’s third generation owner, sold his books too cheaply. After a while I saw that he was spot on, the best bookseller I could ever imagine to have come across. His instinct was for fast turnover at a time when three or four van loads, stacked to the rooftop, would be bought and ferried back to the shop each week. His own interests were computer programming (in its early pirate days), indolence and science fiction. In those days science fiction lovers always had a beard; it was said Nick fed his each evening with John Innes potting compost no.4, the Percy Thrower of bookselling. The shop was a red carpet for the imagination with a wholesome interest in subjects like natural history and bird watching (the feathered kind, though bookshops are three-dimensional, mobile dating sites as well); it was certainly neither stuffy nor elitist. It had accumulated over the years books from the personal libraries of Edgar Wallace, Bernard Shaw and Sir Francis Chichester. Weatherhead’s was a huge operation: antiquarian books upstairs (where its catalogues, which generated much foreign trade, were printed on an ancient Roneo), its turnover doubled by library supply, a vast stock downstairs (both new and second-hand), and a massive warehouse in what was the old town abattoir, the hooks and chains still hung from the ceiling (a previous alternative store had burnt to ash). As many as half-dozen trade dealers were in the shop at any time. The shop was always massively busy when I started to work there, especially on a Saturday when it was swamped with people routinely. It was a playground for truant husbands, hiding from the wife who was shopping elsewhere. The bookshop had opened after the First World War in Folkestone. It moved to Aylesbury at the beginning of the Second World War to escape the bombing. The original site was round the corner to Kingsbury, but it swapped its smaller building for a much larger one when the war had finished, a hat shop, and much of its original first floor shelving above was kept, though far too deep and tall for books. They had a shop in High Wycombe as well for a time.

I worked at Weatherhead’s Bookshop in Kingsbury, Aylesbury for a few years, the most amazing experience. I began my time there haughty and superior, and I felt that Nick Weatherhead, the family’s third generation owner, sold his books too cheaply. After a while I saw that he was spot on, the best bookseller I could ever imagine to have come across. His instinct was for fast turnover at a time when three or four van loads, stacked to the rooftop, would be bought and ferried back to the shop each week. His own interests were computer programming (in its early pirate days), indolence and science fiction. In those days science fiction lovers always had a beard; it was said Nick fed his each evening with John Innes potting compost no.4, the Percy Thrower of bookselling. The shop was a red carpet for the imagination with a wholesome interest in subjects like natural history and bird watching (the feathered kind, though bookshops are three-dimensional, mobile dating sites as well); it was certainly neither stuffy nor elitist. It had accumulated over the years books from the personal libraries of Edgar Wallace, Bernard Shaw and Sir Francis Chichester. Weatherhead’s was a huge operation: antiquarian books upstairs (where its catalogues, which generated much foreign trade, were printed on an ancient Roneo), its turnover doubled by library supply, a vast stock downstairs (both new and second-hand), and a massive warehouse in what was the old town abattoir, the hooks and chains still hung from the ceiling (a previous alternative store had burnt to ash). As many as half-dozen trade dealers were in the shop at any time. The shop was always massively busy when I started to work there, especially on a Saturday when it was swamped with people routinely. It was a playground for truant husbands, hiding from the wife who was shopping elsewhere. The bookshop had opened after the First World War in Folkestone. It moved to Aylesbury at the beginning of the Second World War to escape the bombing. The original site was round the corner to Kingsbury, but it swapped its smaller building for a much larger one when the war had finished, a hat shop, and much of its original first floor shelving above was kept, though far too deep and tall for books. They had a shop in High Wycombe as well for a time.

When at Weatherhead’s in my neophyte days, I got to know Peter Eaton. He was in many ways the respectable criminal manqué and zealous doyen of the second-hand book trade. He had walked from Lancashire to London when a young man, sold books at first from a barrow on the Portobello Road, opened his first shop in Kensington High Street; his last London shop, stylish with pot plants, was in Holland Park, but he had also The Lilies at Weedon, a huge mansion three miles from Aylesbury; here he stored his reserve stock which had previously been strewn like confetti all over London. The house might have been home to Benes and the Czechoslovak or some such government during the Second World War War, I think; it had certainly been a hospital. Eaton had put its boundaries firmly on the map: he was conducting a parochial, vociferous vendetta against the local hunt, and he took no prisoners in a time when hunting was the pastoral preserve of the Shire communities, for which he made the local newspapers often. The huge house had been recommended to Eaton by Frank Weatherhead, Nick’s father; the agreement was that he would not poach on the Weatherhead business. Although the Lilies was intended to be Eaton’s storeroom and country retreat, it came to be known as the largest bookshop in the United Kingdom. One of his trade specialities was ransacking public libraries, buying their cast-off stock at knock-down price. Some of my Oxford tutors would motor to The Lilies, though an appointment was advisable always. When there they would be delighted to be summoned by bell to the drawing room for mid-afternoon tea, bone china and digestive biscuits; then they would resume their addiction and hunt through the twenty or so capacious rooms, each flooded with stock, also the huge basement; they would leave with a car boot full of books. Peter Eaton was a fascinating man: a biographer of Marie Stopes, a friend to many literary glitterati, a confidant to the bookish Michael Foot, and a devotee of the Powys brothers (John Cowper’s death mask was on display on the top floor where Eaton had a tag, rag and bobtail of a museum, its exhibits as idiosyncratic as its curator; the highlights were King George VI’s ration book and “the clock that belonged to the people who put the engine in the boat Shelley drowned in”). Eaton, as I remember him, always with a chequered shirt and squinting, glasses waved aloft, was scruffy and misanthropic, the distillation of the bookseller to his or her purest form. His disdain for customers was legendary; but he was a bluster and bluff gentleman, decorously civil as I watched him once barter with another bookseller for two suitcases full to the brim with first editions of the Powys brothers, all in good condition with their dust jackets; decades of negotiating skill and wheedling guaranteed him the best price. (His wife, Margaret, guarded the fort in his latter days; she was truly game for a bargain too, but fair when needed.) He concerned himself in old age, I think, with his radical obsessions: all booksellers in their purest form are left wing distillations, even Communist if allowed to set like jelly in the fridge. He would speak openly of his nefarious bookselling past, also with jaded scorn of the new breed of educated, parvenu bookseller who held their job to be a calling.

When at Weatherhead’s in my neophyte days, I got to know Peter Eaton. He was in many ways the respectable criminal manqué and zealous doyen of the second-hand book trade. He had walked from Lancashire to London when a young man, sold books at first from a barrow on the Portobello Road, opened his first shop in Kensington High Street; his last London shop, stylish with pot plants, was in Holland Park, but he had also The Lilies at Weedon, a huge mansion three miles from Aylesbury; here he stored his reserve stock which had previously been strewn like confetti all over London. The house might have been home to Benes and the Czechoslovak or some such government during the Second World War War, I think; it had certainly been a hospital. Eaton had put its boundaries firmly on the map: he was conducting a parochial, vociferous vendetta against the local hunt, and he took no prisoners in a time when hunting was the pastoral preserve of the Shire communities, for which he made the local newspapers often. The huge house had been recommended to Eaton by Frank Weatherhead, Nick’s father; the agreement was that he would not poach on the Weatherhead business. Although the Lilies was intended to be Eaton’s storeroom and country retreat, it came to be known as the largest bookshop in the United Kingdom. One of his trade specialities was ransacking public libraries, buying their cast-off stock at knock-down price. Some of my Oxford tutors would motor to The Lilies, though an appointment was advisable always. When there they would be delighted to be summoned by bell to the drawing room for mid-afternoon tea, bone china and digestive biscuits; then they would resume their addiction and hunt through the twenty or so capacious rooms, each flooded with stock, also the huge basement; they would leave with a car boot full of books. Peter Eaton was a fascinating man: a biographer of Marie Stopes, a friend to many literary glitterati, a confidant to the bookish Michael Foot, and a devotee of the Powys brothers (John Cowper’s death mask was on display on the top floor where Eaton had a tag, rag and bobtail of a museum, its exhibits as idiosyncratic as its curator; the highlights were King George VI’s ration book and “the clock that belonged to the people who put the engine in the boat Shelley drowned in”). Eaton, as I remember him, always with a chequered shirt and squinting, glasses waved aloft, was scruffy and misanthropic, the distillation of the bookseller to his or her purest form. His disdain for customers was legendary; but he was a bluster and bluff gentleman, decorously civil as I watched him once barter with another bookseller for two suitcases full to the brim with first editions of the Powys brothers, all in good condition with their dust jackets; decades of negotiating skill and wheedling guaranteed him the best price. (His wife, Margaret, guarded the fort in his latter days; she was truly game for a bargain too, but fair when needed.) He concerned himself in old age, I think, with his radical obsessions: all booksellers in their purest form are left wing distillations, even Communist if allowed to set like jelly in the fridge. He would speak openly of his nefarious bookselling past, also with jaded scorn of the new breed of educated, parvenu bookseller who held their job to be a calling.

In my halcyon days of book buying, the late 1970s, Oxford included more than a few ‘aristocratic’ booksellers of calling. Many of its bookshops were high up the bookselling ladder, although they comprised a broad church of personality, resonance and outlook. This included knowledgeable, nouveau starlets like Peter Hill, my contemporary at Oxford, and Marcus Niner whose modest book hovel was in the High, opened a few years after I left college; they were always keen to buy but never seen to sell (their white rabbit custom they kept hidden up their sleeve), especially keen on polar travel and ‘topography’ – this a term of gravitas; later the less ornate ‘local interest’ came to be used, a nomenclature that signified the dumbing down of both bookselling and society. The pair was as safe as Arsenal’s flat back four, a dream team of the trade. Peter was hunter-gatherer, his peripatetic ways kept him on the road to scour the country for stock, to return with his trophy like a cat with a rat; Marcus was the housewife, hoovering and dusting, and kept the home fire burning. Also the Classics Bookshop at the corner of the Turl, a nicely proportioned bookshop with a balustrade, very theatrical if not authentically Shakespearean, rows and rows of Loebs racked like deck chairs on a sunny day at the seaside; you imagined only ink and quill were used, never a Biro, blotting paper and cake taken with their afternoon tea. Proper antiquarian bookshops were spread over the Turl and other pedestrian backwaters, as shunned as cemeteries, disturbed only by those with interests as alabaster and derelict as death. Their owners, who habitually wore white gloves to avoid inflicting damage upon their relics, were as humdrum as incunabulum; they would turn the pages of books delicately and perversely as though they were fondling the Holy Ghost, and would recite bibliographies instead of prayers at bookshop evensong.

The war horse that was Thornton’s, at this time in its dotage, old man Thornton similarly (he it was seated and dozing at its back desk), was gloriously tumbledown, positioned like a trade gendarme in the centre of the Broad. Various tributaries flowed from its cashpoint delta, and it was arranged as defiant as a musical coda with no resolution. A sequential roster of rooms, big or small, that had as many books laid on the floor in front of the book shelves as upon them; connected by staircases, resting spaces to recover your breath; littered with nooks and crannies, some so tight that you could barely breathe when inside them. It was a many tiered, multi-volume scrum that defied health and safety yet always made perfect sense to the true bibliophile, who needed no compass to steer a course from reportage to belles lettres, through the literary criticism, stopping off at French modernist poetry, though never finding a fire exit – the shop’s undoing in the end. The shop may have been less exciting than I describe, but I fancy it may have taken Stanley longer to find Livingstone inside it than in the African jungle. I recall Brian Aldiss’ first novel, The Brightfount Diaries, was set here; he had worked there in the 1950s.

The war horse that was Thornton’s, at this time in its dotage, old man Thornton similarly (he it was seated and dozing at its back desk), was gloriously tumbledown, positioned like a trade gendarme in the centre of the Broad. Various tributaries flowed from its cashpoint delta, and it was arranged as defiant as a musical coda with no resolution. A sequential roster of rooms, big or small, that had as many books laid on the floor in front of the book shelves as upon them; connected by staircases, resting spaces to recover your breath; littered with nooks and crannies, some so tight that you could barely breathe when inside them. It was a many tiered, multi-volume scrum that defied health and safety yet always made perfect sense to the true bibliophile, who needed no compass to steer a course from reportage to belles lettres, through the literary criticism, stopping off at French modernist poetry, though never finding a fire exit – the shop’s undoing in the end. The shop may have been less exciting than I describe, but I fancy it may have taken Stanley longer to find Livingstone inside it than in the African jungle. I recall Brian Aldiss’ first novel, The Brightfount Diaries, was set here; he had worked there in the 1950s.

The more functional and economical Robin Waterfield’s was toward the railway station and escape to the outside world; its broom cupboard first floor entrance was in denial of its vast stretch above and beyond. Its supposed regard for book democracy and the common man was a cynical strategy, commercial and careless: it paraded itself as the antidote to pretension by mixing the commonplace with the august, confusing the cheap and tatty with the collectible and prized. I didn’t think that much of the shop and am not sure why that was so, but I assumed that they paid for their stock by the weight rather than by content (and when I sold books to them later, I discovered that they did – the weightier the collection, the less they paid, the perfect antidote to ordinance and good sense). I felt it improved greatly when it resited at the bottom of the High and took on more didactic ways; in fact its final owner closed the shop to become a teacher.

For the armchair revolutionary there was The Little Bookshop in the covered market, an unwholesome, chaotic mash of used claptrap – Lenin, Trotsky, paperback sets of Braudel’s History of the Mediterranean at bargain price, Mills and Boon, all sorts – but in retrospect remembered anecdotally and affectionately so often for startling finds (and for Garon Records next door). Further away up the Cowley Road were occasional smatterings of real radicalism, feminism and the arcane.

For the armchair revolutionary there was The Little Bookshop in the covered market, an unwholesome, chaotic mash of used claptrap – Lenin, Trotsky, paperback sets of Braudel’s History of the Mediterranean at bargain price, Mills and Boon, all sorts – but in retrospect remembered anecdotally and affectionately so often for startling finds (and for Garon Records next door). Further away up the Cowley Road were occasional smatterings of real radicalism, feminism and the arcane.

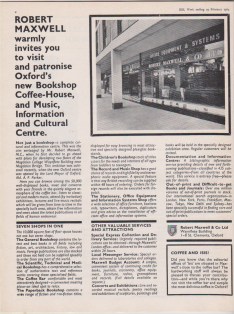

I recall also Robert Maxwell’s innovatory shop on the Plain which sold new books only (and typewriters), but it had sofas and other ergonomic obstacles, coffee was served there and I remember my family called in often; I was surprised to read that it closed much earlier in 1972, though not surprised that it had traded at a severe loss, just as had Maxwell’s innovatory book wholesale escapade in the 1950s. Also there were the two Catholic bookshops off the bottom of St Aldates, which I liked, both of which were staffed by Graham Greene lookalikes with horn-rimmed glasses. The lesson I took away from these shops is that you can have too much Chesterton. Non-heretical theological bookshops could be found for the clever clog and apologetic Anglican vicars who mysteriously had briefcases as well as clergy dog collars, pince-nez poised on their nose like parables. Remainder bookshops sprung up slapdash like daffodils in spring only to wither as quickly. It seemed as though every book ever published was available somewhere in Oxford at that time.

I recall also Robert Maxwell’s innovatory shop on the Plain which sold new books only (and typewriters), but it had sofas and other ergonomic obstacles, coffee was served there and I remember my family called in often; I was surprised to read that it closed much earlier in 1972, though not surprised that it had traded at a severe loss, just as had Maxwell’s innovatory book wholesale escapade in the 1950s. Also there were the two Catholic bookshops off the bottom of St Aldates, which I liked, both of which were staffed by Graham Greene lookalikes with horn-rimmed glasses. The lesson I took away from these shops is that you can have too much Chesterton. Non-heretical theological bookshops could be found for the clever clog and apologetic Anglican vicars who mysteriously had briefcases as well as clergy dog collars, pince-nez poised on their nose like parables. Remainder bookshops sprung up slapdash like daffodils in spring only to wither as quickly. It seemed as though every book ever published was available somewhere in Oxford at that time.

And, of course, the Mecca of the trade, Basil Blackwell’s, still owned by the founder’s family, which at this point threatened to ram the city centre with bookshops. Its gargantuan headquarters were at one end of Broad Street leaning against the Weston Library and dug in just as deep, prepared as though for battlefield skirmish: the Norrington Room, the biggest book room in the world, is its bookish bunker, a war room trench tunnelled under Trinity College; its dimensions are based clearly on the battlefield at Agincourt. (Each St Crispin’s Day the current Mr Blackwell will charge the French still by donating a hefty part of his dividend to U.K.I.P. I disagree totally with the lame and immature calls to boycott the shop.) Blackwell’s reconnaissance satellites which sold new books sprawled the length of the Broad. Parker’s was select, precise, its shoes polished, catering for its library clientele on the opposite side of the road; the paperback shop that opened dangerously late into the early evening, defying martial law and curfew, was nearby; the children’s outpost further down, the recruiting office, not as avuncular as it might be, for it was designed for anyone but children (grandmother’s buy most children’s books, only booksellers know that). The jewel of Blackwell’s military machine, for me at least, was the music shop in Holywell Street which whiled away many of my hours each week, a musical slot machine that I fed with much of my grant money; I ricocheted around its vinyl stash, and, three to the bar, would sashay round its second-hand sheet music, which looped its basement mezzanine like an interminable Chopin Waltz. The music department today is a melee of excellence, specialist knowledge and unbelievable service: it is hard to imagine that there is a shop better than this in the whole of Britain. In the main shop, Blackwell’s buying policy for used books was insane. You were made to queue whilst their two buyers interrogated the books as though at court marshal; they paid by the footnote, so a fortune could be made with recently published heavyweight opus, and I had no idea how they got to make much money out of the transaction. They had also an antiquarian bookshop housed out of Oxford.

And, of course, the Mecca of the trade, Basil Blackwell’s, still owned by the founder’s family, which at this point threatened to ram the city centre with bookshops. Its gargantuan headquarters were at one end of Broad Street leaning against the Weston Library and dug in just as deep, prepared as though for battlefield skirmish: the Norrington Room, the biggest book room in the world, is its bookish bunker, a war room trench tunnelled under Trinity College; its dimensions are based clearly on the battlefield at Agincourt. (Each St Crispin’s Day the current Mr Blackwell will charge the French still by donating a hefty part of his dividend to U.K.I.P. I disagree totally with the lame and immature calls to boycott the shop.) Blackwell’s reconnaissance satellites which sold new books sprawled the length of the Broad. Parker’s was select, precise, its shoes polished, catering for its library clientele on the opposite side of the road; the paperback shop that opened dangerously late into the early evening, defying martial law and curfew, was nearby; the children’s outpost further down, the recruiting office, not as avuncular as it might be, for it was designed for anyone but children (grandmother’s buy most children’s books, only booksellers know that). The jewel of Blackwell’s military machine, for me at least, was the music shop in Holywell Street which whiled away many of my hours each week, a musical slot machine that I fed with much of my grant money; I ricocheted around its vinyl stash, and, three to the bar, would sashay round its second-hand sheet music, which looped its basement mezzanine like an interminable Chopin Waltz. The music department today is a melee of excellence, specialist knowledge and unbelievable service: it is hard to imagine that there is a shop better than this in the whole of Britain. In the main shop, Blackwell’s buying policy for used books was insane. You were made to queue whilst their two buyers interrogated the books as though at court marshal; they paid by the footnote, so a fortune could be made with recently published heavyweight opus, and I had no idea how they got to make much money out of the transaction. They had also an antiquarian bookshop housed out of Oxford.

Blackwell’s, at least when I was young and eager, was at ease with its donnish fervour, speckled like heady, dense dust on its shop fitting and stock. It is not quite so couth and shevelled today, for there is a sense of unease, a sense that its staid ownership, weighted with family resolve and the laziness of inherited wealth (and its building’s freehold), tussle with its enthusiastic and keen staff. Its library business, I guess, is still more or less secure, at least while the excess of libraries in Oxford retain analogue breath; this part of their trade is like the hidden wealth made by Coleman’s mustard – more is left on the side of the plate than is ever tasted, and similarly most of the books in Oxford’s libraries I suspect are as skeletons in graveyard vaults, that is their covers are rarely, if ever, to be prised apart. To such a lofty, clever and reverential hinterland, Blackwell’s will appeal still for it has the cache of tradition. Its rooms, walls, shelves of books have been lined with alphabetic purpose and sit upright as guardsmen on duty for over a hundred years; to parade around its syllabary soup is a Grand Literary Tour. This has always been the most impressive flock wallpaper known to the world. If Blackwell’s no longer thrives as it once did (its accounts are unshook foil) and if to extract money from the shop for your box of second-hand books is all but miraculous, it can still hold its own – but only just, like a punch drunk boxer still in the ring because he was never trained to fall to the canvas. Today it is less sombre in aspect, though the finish of its décor is still chosen from an undertaker’s office. It is also less deferential and has no circular front desk with its team of respectful staff, as it did decades before, each staff mimicking the aspect of a porter or scout in one of the colleges. The shop still has queues, of which I was deeply envious! These queues are fed like birds in the park, its crumbs are the books that litter the front tables and shelving – popular literature with cheerful covers. In my pubescent youth its entrance was as a grand

Blackwell’s, at least when I was young and eager, was at ease with its donnish fervour, speckled like heady, dense dust on its shop fitting and stock. It is not quite so couth and shevelled today, for there is a sense of unease, a sense that its staid ownership, weighted with family resolve and the laziness of inherited wealth (and its building’s freehold), tussle with its enthusiastic and keen staff. Its library business, I guess, is still more or less secure, at least while the excess of libraries in Oxford retain analogue breath; this part of their trade is like the hidden wealth made by Coleman’s mustard – more is left on the side of the plate than is ever tasted, and similarly most of the books in Oxford’s libraries I suspect are as skeletons in graveyard vaults, that is their covers are rarely, if ever, to be prised apart. To such a lofty, clever and reverential hinterland, Blackwell’s will appeal still for it has the cache of tradition. Its rooms, walls, shelves of books have been lined with alphabetic purpose and sit upright as guardsmen on duty for over a hundred years; to parade around its syllabary soup is a Grand Literary Tour. This has always been the most impressive flock wallpaper known to the world. If Blackwell’s no longer thrives as it once did (its accounts are unshook foil) and if to extract money from the shop for your box of second-hand books is all but miraculous, it can still hold its own – but only just, like a punch drunk boxer still in the ring because he was never trained to fall to the canvas. Today it is less sombre in aspect, though the finish of its décor is still chosen from an undertaker’s office. It is also less deferential and has no circular front desk with its team of respectful staff, as it did decades before, each staff mimicking the aspect of a porter or scout in one of the colleges. The shop still has queues, of which I was deeply envious! These queues are fed like birds in the park, its crumbs are the books that litter the front tables and shelving – popular literature with cheerful covers. In my pubescent youth its entrance was as a grand  vestibule, as auspicious as a railway station once was and as solemn as the bank manager’s waiting room; all was hushed reverence as a welter of staff pilfered the filing cabinets to locate details of your account. To open a Blackwell’s account was a rite of passage in your University life, second perhaps to acceptance as a member of the Bodleian Library. The only book I ever took on account was A. J. P. Taylor’s wonderful book on the Hapsburg Empire and German unification, his clipped style and roving eye elevating otherwise dreary tales of diplomatic and military middle Europe to flights of imagination. I made such a hash of settling the account that I was too ashamed to use it again; I’d have been useless as Bismarck also.

vestibule, as auspicious as a railway station once was and as solemn as the bank manager’s waiting room; all was hushed reverence as a welter of staff pilfered the filing cabinets to locate details of your account. To open a Blackwell’s account was a rite of passage in your University life, second perhaps to acceptance as a member of the Bodleian Library. The only book I ever took on account was A. J. P. Taylor’s wonderful book on the Hapsburg Empire and German unification, his clipped style and roving eye elevating otherwise dreary tales of diplomatic and military middle Europe to flights of imagination. I made such a hash of settling the account that I was too ashamed to use it again; I’d have been useless as Bismarck also.

The national closure of such myriad second-hand and antiquarian bookshops has decimated this bookselling ladder. Also the decline of the book fair, motley, specialist dealers assembled in village halls or posh hotel foyers. The Randolph Hotel was where the venerable Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association would meet. To join the ABA was as demanding as MENSA; but once accepted, a member was expected to dress like a quarter bound folio edition with bow tie and a shirt cut from marbled endpaper. The Association’s members had probably been school prefects and first team rugby players who, removed from their school greenhouse of promise, ill-prepared to be potted on into the garden outside with its inclement weather, had bolted like lettuce left in the ground until late September, and had to a man taken to drink. They all had immense corporations decorated with pocket watches and chains; they all knew who Jorrocks and Samuel Richardson were, and were usually so dotty that they assumed everybody else did too. The death of the Royal Mail and of its printed matter rate (the specialist book dealer sold often from mail order catalogues), as well this bibulous aspect, killed off many of these booksellers. Nonetheless it is only antiquarian books which have held their value over the decades, unlike all other books whose worth plummets by the hour. Today’s book world resembles hyper-inflationary Weimar Germany: a wheelbarrow of books cannot be traded even for a loaf of bread. There are not many second-hand bookshops left in Oxford, 2018. The internet is probably the main cause for this decline, although I am not so sure we should credit it with every change in society. Sometimes a coiled string will unravel of its own accord. Stuff the reading of them – not that many people read the books they buy – the book itself has come to hold a different meaning than before in our present society.