The Albion Beatnik Bookstore website (or how to change a light bulb in a tight space on a ladder)

The web page of the Albion Beatnik Bookstore, based once in Oxford, then Sibiu, always neo-bankrupt, now closed for business: atavistic and very analogue, its musings and misspells on books and stuff.

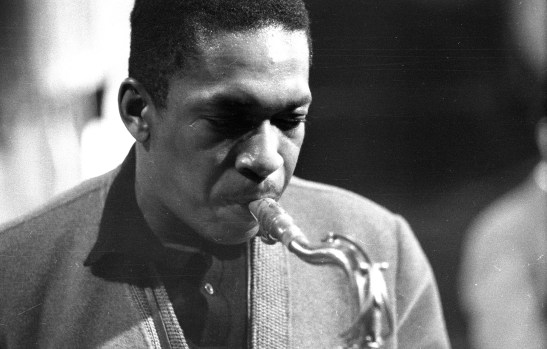

Spiritual Synaesthesia: John Coltrane at Ninety

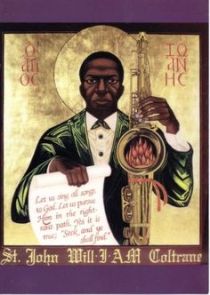

In a brief and urgent career, John Coltrane transformed jazz and became a beacon for much else; he died aged only forty in 1967. A spiritual awakening in 1957 removed from him the narcotic and alcoholic fix that had featured previously in his life, a story retold in his classic album A Love Supreme, and at this time he transferred his impulse from the purely musical to the mystical and accidentally canonical (indeed he did remark casually that he wished to become a saint). The pyrotechnics of his improvisation – flagrant, vast and helter-skelter – ascended to a higher dimension, a musical and spiritual synaesthesia where his world of the divine became fortified with scales and arpeggios, and the incorporeal drove his musical quest. A taste for world religion and an interest in an early variant of world music followed; there was, too, an afterlife of iconic revelry. Raga, modes and musical voodoo were for Coltrane the architecture that produced “specific emotional meanings,” and musically he desired to “discover a method so that if I want it to rain, it will start right away to rain.” He espoused a belief “in all religions;” he popped Hinduism, Plato and the Bhagavad Gita, Jiddu Krishnamurti, African history and Zen Buddhism as once he had popped pills. After he died of liver cancer in 1967 he received incantation from San Francisco’s Yardbird Temple (they interpreted Charlie Parker as John the Baptist and Coltrane as God Incarnate – JC the initials of both John Coltrane and Jesus Christ, which to some is as spooky as the Bermuda Triangle or the grassy knoll); the church of Coltrane was affiliated later into the African Orthodox Church, he was demoted then to sainthood, but still today his music and words form part of a Sunday liturgy for fifteen parishes and over 5,000 souls who recite his words and play his music in a Jehovah-like jam session, quite literally. For believers, the good news is that in the family vaults lie unreleased material, a sort of belated Apocrypha, and his son Ravi is set to release them in time (the first in 1995) as though manna from heaven or, for the family at least, pennies from heaven. It’s impossible today to be cool and not to pretend to like his music. In truth, nostalgia and an early death (the James Dean/John Lennon act of creative mythology) have done nothing to further his appeal, for Coltrane was always cool. Miles Davis alluded to this transcendence when, not longer after they had gone their separate ways, he claimed that his own late 1950s quintet had “made me and him a legend,” Davis and Coltrane the two greater godheads in a trinity that in time would include Ornette Coleman as the shape-shifters of post-bebop jazz.

In a brief and urgent career, John Coltrane transformed jazz and became a beacon for much else; he died aged only forty in 1967. A spiritual awakening in 1957 removed from him the narcotic and alcoholic fix that had featured previously in his life, a story retold in his classic album A Love Supreme, and at this time he transferred his impulse from the purely musical to the mystical and accidentally canonical (indeed he did remark casually that he wished to become a saint). The pyrotechnics of his improvisation – flagrant, vast and helter-skelter – ascended to a higher dimension, a musical and spiritual synaesthesia where his world of the divine became fortified with scales and arpeggios, and the incorporeal drove his musical quest. A taste for world religion and an interest in an early variant of world music followed; there was, too, an afterlife of iconic revelry. Raga, modes and musical voodoo were for Coltrane the architecture that produced “specific emotional meanings,” and musically he desired to “discover a method so that if I want it to rain, it will start right away to rain.” He espoused a belief “in all religions;” he popped Hinduism, Plato and the Bhagavad Gita, Jiddu Krishnamurti, African history and Zen Buddhism as once he had popped pills. After he died of liver cancer in 1967 he received incantation from San Francisco’s Yardbird Temple (they interpreted Charlie Parker as John the Baptist and Coltrane as God Incarnate – JC the initials of both John Coltrane and Jesus Christ, which to some is as spooky as the Bermuda Triangle or the grassy knoll); the church of Coltrane was affiliated later into the African Orthodox Church, he was demoted then to sainthood, but still today his music and words form part of a Sunday liturgy for fifteen parishes and over 5,000 souls who recite his words and play his music in a Jehovah-like jam session, quite literally. For believers, the good news is that in the family vaults lie unreleased material, a sort of belated Apocrypha, and his son Ravi is set to release them in time (the first in 1995) as though manna from heaven or, for the family at least, pennies from heaven. It’s impossible today to be cool and not to pretend to like his music. In truth, nostalgia and an early death (the James Dean/John Lennon act of creative mythology) have done nothing to further his appeal, for Coltrane was always cool. Miles Davis alluded to this transcendence when, not longer after they had gone their separate ways, he claimed that his own late 1950s quintet had “made me and him a legend,” Davis and Coltrane the two greater godheads in a trinity that in time would include Ornette Coleman as the shape-shifters of post-bebop jazz.

When Davis plucked Coltrane from obscurity in the mid-1950s, his muscular tone and new found technical brilliance shocked critics and helped cast a shadow of expectation: he was apart from the rest, and that Coltrane would deliver became a truism. In time he became a leading exponent of modal improvisation and a prophet of the jazz avant-garde. The buzzword used most often with Coltrane is intensity: a desire to travel beyond melody, harmony and rhythm, to reach the Shangri-la of emotion, a visceral and ethical form of music making. Long and tortuous hours of practice, coinciding with his spiritual epiphany, had developed a commanding technique. When applied with a relentless vigour it is a technique of transubstantiation and becomes one with emotional lust. It could be argued that it was resolute pyrotechnic before any emotional intensity that is the keystone of what jazz critic Ira Gitler called Coltrane’s “sheets of sound,” voluminous, rapid notes that dissect a chord or scale as a scalpel (often with scant melodic or rhythmic developments). But however one gauges Coltrane’s musical language and sonority, at the heart of his playing is always the roots of jazz, the call and response gospel sound of the blues and an attempt to emulate the human voice, in fact the childish jungle sound of Bubber Miley in Ellington’s early band. Coltrane was of the essence and a genius. Despite his technical mastery and its relentless vigour, simplicity was his crux, and this is the paradox of his playing, a paradox that endeared him so readily to the American youth of the 1960s and beyond.

When Davis plucked Coltrane from obscurity in the mid-1950s, his muscular tone and new found technical brilliance shocked critics and helped cast a shadow of expectation: he was apart from the rest, and that Coltrane would deliver became a truism. In time he became a leading exponent of modal improvisation and a prophet of the jazz avant-garde. The buzzword used most often with Coltrane is intensity: a desire to travel beyond melody, harmony and rhythm, to reach the Shangri-la of emotion, a visceral and ethical form of music making. Long and tortuous hours of practice, coinciding with his spiritual epiphany, had developed a commanding technique. When applied with a relentless vigour it is a technique of transubstantiation and becomes one with emotional lust. It could be argued that it was resolute pyrotechnic before any emotional intensity that is the keystone of what jazz critic Ira Gitler called Coltrane’s “sheets of sound,” voluminous, rapid notes that dissect a chord or scale as a scalpel (often with scant melodic or rhythmic developments). But however one gauges Coltrane’s musical language and sonority, at the heart of his playing is always the roots of jazz, the call and response gospel sound of the blues and an attempt to emulate the human voice, in fact the childish jungle sound of Bubber Miley in Ellington’s early band. Coltrane was of the essence and a genius. Despite his technical mastery and its relentless vigour, simplicity was his crux, and this is the paradox of his playing, a paradox that endeared him so readily to the American youth of the 1960s and beyond.

The simplicity of this wellspring sat ill at ease with his searing intent; his quest for jazz Arcadia was vaulting ambition, an ambition as sincere as it was flawed. The ambition flowered with the lengthy track Om, recorded in late 1965, a depiction of the sacred syllable in Hinduism, incorporating chants and recitation from The Tibetan Book of the Dead. The flaw is best summed up by the legendary exchange between Coltrane and Miles Davis. Miles’ quintet at times was exasperated by Coltrane who could tease a phrase seemingly forever as he ushered cascading volleys of musical fare. Coltrane turned on this criticism with a personal and defiant logic, explained that he just didn’t know how to stop such maelstrom. To which Miles responded with a typical truth: “try taking the fucking horn out of your mouth.” Yin and yang: every yogi distils to self, every spirit belongs to a body.