The Albion Beatnik Bookstore website (or how to change a light bulb in a tight space on a ladder)

The web page of the Albion Beatnik Bookstore, based once in Oxford, then Sibiu, always neo-bankrupt, now closed for business: atavistic and very analogue, its musings and misspells on books and stuff.

The Legend of St Elmo: Elmo Hope & Bebop Piano

ELMO HOPE is seemingly a forgotten pianist of the bebop era. His unfulfilled musical life tells us much about the jazz experience of 1950s America, but much more about the superficial nature of jazz research today….

The musical tragedy of Elmo Hope, an accomplished bebop pianist who made a peripheral impression on the jazz scene of the 1950s, teaches us much about the jazz world he inhabited. He was sidelined when bebop was in its creative heyday and found little favour when the opportunity to shine came his way. His life was largely undocumented and his work mostly uncelebrated. His bibliography consists of brief album liner notes and a few titbits, and only one interview was published – in Down Beat magazine in 1961, where its subject left the impression of a life unfulfilled, clouded with personal bitterness about both his circumstance and his musical environment. At that time Hope was waylaid on the West Coast having been denied his cabaret card in New York for narcotic offences, and being in the wrong place seems to have been the tide that governed his life. If his musical friends, among them Bud Powell, were making a name on 52nd Street, Hope was performing in the dance halls of Greenwich Village and Coney Island; if his colleagues were taking the bebop creed to a wider audience, Hope was touring the provinces with a rhythm and blues band; and if the momentum had shifted back to New York, Hope was marooned on, at least as far as he was concerned, the musically sterile West Coast. Why Hope made little headway in the jazz scene of the 1940s is a point to be debated. His technique was as sufficient as many other bebop pianist of his time and place, his performance as polished, his compositions and arranging prowess as accomplished, yet something in his hull was not watertight. That the 1950s was unable to offer him a second bite of the cherry is not so surprising: the jazz world had moved on, and his syle of playing never developed sufficiently to circle a larger orbit. Some of his keyboard contemporaries had been able to ride on the coat tails of a major star – Richie Powell with Clifford Brown, Walter Bishop briefly with Parker, and, later, Red Garland with Miles Davis; others, such as Dodo Marmarosa, fell by the wayside; and others, like Al Haig and Mal Waldron, hung in long enough to find a minor place in the annals of jazz. None of these happened to Elmo Hope: he was never able to hitch a ride with a major star, saw his brief musical odyssey through to its end, and died in obscurity before his forty-fourth birthday. A life crowned with promise and little achievement, the legend of Elmo Hope is indicative not just of this particular pianist’s mix of mishap and flaw, but of the misfortune and shortcoming of the bebop pianist in general, his repertoire, his narrow approach, and his cruel environment.

Hope’s wife and fellow pianist Bertha (they married in 1960) helped to keep his music in the public domain, touring with both her own quartet and a repertory band called ELMOllenium. The digital age has encouraged reissues of some (not all) of his scant recordings, and he is mentioned in the plethora of jazz history books that have been published since his death in brief yet glowing terms, all with a similar recital of stock phrases and stories, and these mostly gleaned from album liner notes. At best this is a fragment of a life; at worst apocryphal and ultimately disrespectful, for the clichés have been used as a smokescreen to hide inadequate and spurious research in to his life and times.

Elmo Hope was born in New York, 1923. He was christened St Elmo, the patron saint of sailors. He started to learn the piano from the age of seven, and all the commentaries highlight his being nurtured in the classics and meeting some local success in schoolboy competitions, although Hope later in life was to claim that he was self-taught. Musicians of an earlier generation – Billy Kyle or Clyde Hart, for instance – were torn between the stock language of swing and the bright new sounds of what flowered as the bebop style. Hope and his contemporaries, at least those in New York, were seduced easily by the bold sounds being produced by Parker and Gillespie and being worked through at after-hours sessions at Minton’s Playhouse. A friend from his schooldays was Bud Powell, and Powell was later to introduce Hope to Thelonious Monk. The three were referred to as the Three Musketeers kept each other’s company and compared musical notes; one fellow pianist of this period, Bob Bunyan, recalled how “Bud had got the powerful attack and Elmo got into some intricate harmonies.” However the glories are shared, it should not be doubted that Hope played a part at the wellspring of bebop piano, however slight or informal.

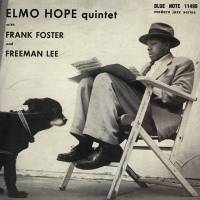

Having worked in the dance halls and clubs away from the jazz centre of New York, which was 52nd Street, Hope went on to tour with trumpeter Joe Morris and recorded with this group in 1948. At various times other members of this band included Johnny Griffin, Percy Heath and Philly Joe Jones, but the musical fare was rhythm and blues and certainly not what Hope was interested in. Further touring ensued with Etta Jones, and it was not until mid-1953, when aged thirty, that Hope was given the opportunity to record in an uncompromised jazz idiom. Alongside Heath and Jones, he supported saxophonist Lou Donaldson and Clifford Brown in a session for Blue Note that produced the Clifford Brown Memorial Album. A further album and two 10″ LPs were issued under his own name, including The Elmo Hope Trio and Quintet.

Hope seems at this stage to have made at least a foothold in the jazz world, and in the next few years he recorded and played with not only Donaldson but Kenny Dorham, Sonny Rollins (on the album Moving Out) and Jacky McLean (Lights Out!). His own trio album Meditations appeared in 1955, and this outing marks Hope’s first serious and public demonstration of his credentials as a composer; five titles on this album, including Elmo’s Fire, were self-penned. Other albums for Prestige ensued: Hope Meets Foster, with Frank Foster on tenor saxophone, and Informal Jazz (1956), billed as the Elmo Hope sextet featuring Donald Byrd and John Coltrane. None of these albums made serious critical inroad and the impression made was mot likely of a pianist punching above his weight; certainly the records did not suggest that they had been carefully thought out and are often referred to disparagingly as ‘blowing sessions’. By this point Hope had lost his cabaret card for drug offences and was not able to perform in New York clubs. In 1957 he toured with Chet Baker, and he settled in Los Angeles where the climate was more kind to the chest infections he was prone to.

Hope seems at this stage to have made at least a foothold in the jazz world, and in the next few years he recorded and played with not only Donaldson but Kenny Dorham, Sonny Rollins (on the album Moving Out) and Jacky McLean (Lights Out!). His own trio album Meditations appeared in 1955, and this outing marks Hope’s first serious and public demonstration of his credentials as a composer; five titles on this album, including Elmo’s Fire, were self-penned. Other albums for Prestige ensued: Hope Meets Foster, with Frank Foster on tenor saxophone, and Informal Jazz (1956), billed as the Elmo Hope sextet featuring Donald Byrd and John Coltrane. None of these albums made serious critical inroad and the impression made was mot likely of a pianist punching above his weight; certainly the records did not suggest that they had been carefully thought out and are often referred to disparagingly as ‘blowing sessions’. By this point Hope had lost his cabaret card for drug offences and was not able to perform in New York clubs. In 1957 he toured with Chet Baker, and he settled in Los Angeles where the climate was more kind to the chest infections he was prone to.

On the West Coast Hope met and married Bertha, managed to find some work (mainly with saxophonist Harold Land but also with Lionel Hampton in 1959) but little musical favour if the interview conducted with Down Beat is to be taken at face value. He recorded with Land, producing the album The Fox and other material, and made two solo albums for the Hifijazz label. It is these two albums, Elmo Hope Trio and So Nice, that exhibit Hope at his best and at his most mature. The sessions were well thought out, his own compositions pushed to the fore, and his trio of Jimmy Bond and Frank Butler worked well as a unit and were more responsive to Hope’s blend of stuttering bebop styles.

On the West Coast Hope met and married Bertha, managed to find some work (mainly with saxophonist Harold Land but also with Lionel Hampton in 1959) but little musical favour if the interview conducted with Down Beat is to be taken at face value. He recorded with Land, producing the album The Fox and other material, and made two solo albums for the Hifijazz label. It is these two albums, Elmo Hope Trio and So Nice, that exhibit Hope at his best and at his most mature. The sessions were well thought out, his own compositions pushed to the fore, and his trio of Jimmy Bond and Frank Butler worked well as a unit and were more responsive to Hope’s blend of stuttering bebop styles.

Hope returned to New York in 1961, having met Orrin Keepnews, head of Riverside records, the previous year. The album Homecoming! was the result, with trumpeter Blue Mitchell as a featured soloist. Again this recording is not the greatest of dates – although more Hope originals, such as La Berthe, were featured – and it met scant critical acclaim. With Hope still unable to perform in licensed premises, he chased work as an arranger within and without the jazz fold, although the level of success he met is unknown.

Other disjointed recording sessions followed in the 1960s: Hope-full (1961), a solo and two piano duet session featuring Bertha, again for Riverside, and Sounds From Riker’s Island (1963) with the longstanding Sun Ra saxophonist John Gilmore, on the Audiofidelity label, where play was made of Hope’s narcotic conviction. Two later trio sessions were made in 1966, although these were issued only posthumously more than a decade later. Elmo Hope’s career petered out through lack of work and ill health. In 1967 he was hospitalized with pneumonia and died from heart failure.

Hope’s life raises many interesting questions about his own career as a jazz artist, but also about the nature of 1940s’ and 1950s’ American jazz. To begin with what was it about Hope that divorced him from the main bebop movement in the mid- to late 1940s in New York? Was he an outsider to the bebop coterie, or was he simply not versatile enough to meet its demands? And, perhaps more controversially, what was it about the bebop piano style that allowed most of its practitioners to be left behind or even forgotten? Many of bebop’s formative saxophonists and brass players carried on with recording careers long after their first flush of bebop activity. Hope’s musical career remained, of course, a fledgling one, but many other pianists who had found work on 52nd Street in the late 1940s found also that the work dried up, as a second generation of pianists from Horace Silver to Wynton Kelly moved in. Aside from the individualism of Thelonious Monk, who gained an audience and praise only much later, and the dynamism of Bud Powell, who could sustain his drive both physically and emotionally for only a brief period and never developed as he might, there are no other bebop pianists of the 1940s who have made a significant mark on jazz history. Individualists like Lennie Tristano or George Shearing veered off in other directions, and Elmo Hope – like George Wallington or Walter Bishop or Duke Jordan or Dodo Marmarosa – has been left in the shadows.

In any case, the life and music of Elmo Hope should not be forgotten: there is much to be learnt from it. Apart from Noal Cohen’s discographical endeavour there is little further research that has stripped away the mythology. Elmo Hope died nearly fifty years ago; many of those who knew him, professionally or otherwise, will be with us no longer, sadly.

excellent reappraisal. some of his left hand work is so strong. and great compositions. thanks.